15. The Power Plants of the Future?

What will they burn instead of coal?’ ‘Water,’ replied Cyrus Harding. ‘Water decomposed into its primitive elements, by electricity, which will then have become a powerful and manageable force’. In the 1875 novel The Mysterious Island, Jules Verne, via his protagonist, envisions hydrogen becoming the fuel of the future. “Clean” hydrogen, which is produced by electrolysis of water, can be used in a to generate electricity or recombined to produce gas. It could therefore become a new fuel, produced, transported and traded around the world, as oil and natural gas are today. This image shows a model of an electrolysis-based hydrogen production unit on display at the Toshiba research center in Tokyo.

1. Wood, the First Energy Source

Humankind’s control of fire can be traced back by studying archaeological remains, including evidence of ancient hearths. It most likely dates back as far as 500,000 years in Europe, 800,000 years in the Middle East, and perhaps more than one million years in Africa. Prehistoric humans used the first form of , wood, which enabled them to warm themselves, create light, cook their food and keep wild animals away. In the Neolithic period (8500-3000 B.C.), our ancestors went beyond hunting and gathering and began to cultivate the land and domesticate animals, which provided a new source of energy for pulling plows and carrying loads. At the end of the Neolithic period, humans gradually learned to harness the of the wind and water and the of the Sun. With each new energy source mastered, humanity made rapid progress. Pictured here is a reconstruction of a prehistoric scene at the National Museum of Mongolian History in Ulaanbaatar.

2. Wind, the Source of Mobility

The construction of sailing boats, using the power of the wind, made it possible for people to expand their territories and discover the world. At its height, between 1500 and 1000 B.C., Egyptian civilization settled all along the Nile. In this photo, a mural discovered in the tomb of the royal scribe Menna shows a large funeral boat taking his body to Abydos, near Luxor, on the banks of the great river. During the same period, the Phoenicians sailed into the Mediterranean Sea from present-day Lebanon and gave rise to modern trade, exchanging goods with increasingly distant countries. Chinese civilization also began along the Yellow River, in 1600 B.C., before establishing the sea and land “Silk Roads”.

3. Water for Building Cities

The watermill is probably older than the windmill. It is mentioned by Vitruvius, a great Roman architect of the 1ST century B.C., in De Architectura. A 3rd century A.D. bas-relief in Hierapolis, Turkey, depicts an ancient water-powered machine using a system of connecting rods and cranks. According to a reconstruction of the design (see image), it operated a pair of saws intended to cut stone. In the following centuries, windmills and watermills would be developed to perform many functions, such as pumping water for cattle and land irrigation, sawing wood and making oils and flours. The windmill became a ubiquitous feature of the coasts of the Netherlands, Denmark, England and Germany, all of which have continued to develop wind technology.

4. Concentrated Energy from the Sun

The use of sunlight as an energy source came later than that of wood, wind and river currents. Legend has it that Archimedes was able to use parabolic mirrors to set fire to the Roman ships laying siege to Syracuse in 213 B.C., but the first real scientific experiments were not until the 18th century. In 1774, Horace-Benedict de Saussure from Geneva designed the “heliothermometer”, the predecessor of the solar collector, with a glass pane placed above an insulated box and a heat absorber. He even considered using double-glazing for better insulation. A little later, Antoine Lavoisier experimented with lenses that, by concentrating the Sun’s rays, could melt pieces of metal (as shown here).

5. The Two Forms of Solar Energy

In 1839, the 19-year-old (!) French physicist Edmond Becquerel discovered the , which allows to be produced from solar radiation. (His son, Antoine, would become a pioneer in .) However, it would take more than a century for this discovery to lead to real applications, after scientists had laid the foundations of nuclear physics and invented semiconductors. Others have attempted to use the heat of the Sun on an industrial scale. In 1878, Augustin Bernard Mouchot built an ingenious machine for the Universal Exhibition in Paris (shown here). It featured a 20-square-meter parabolic solar reflector with a steam engine at its center. Unfortunately, it did not generate a lot of power. Research into solar thermal energy was soon overshadowed by fossil fuels such as and later oil, which are much more efficient.

6. A Truly Brilliant Trailblazer

A Danish meteorologist, Poul La Cour (1846-1908), is considered the pioneer of . He was also one of the first to take an interest in the issue of electricity storage to overcome the problem of intermittency, and he had the idea of using as an intermediate . All of this makes him a true pioneer, especially since he also laid the foundations for telephony. With wind power, La Cour sought to bring electricity to the countryside to improve rural people’s working conditions and to prolong activity during the long winter nights, for example for education. In the beginning, he tried to generate electricity via the country’s many conventional windmills. Then he discovered that by using a blade shape for the sails and reducing their number, it was possible to improve their efficiency.

7. How the Wind Turbine Got Its Shape

Finding the right shape for a wind turbine was a long process. The Ohio-born American Charles F. Brush was instrumental in this process, building what is considered to be the first modern wind turbine in his home in Cleveland in 1888. However, it was not very efficient: the 36-ton machine had a capacity of just 12 kilowatts (the average wind turbine today has a capacity of 2,000 kilowatts). You can get an idea of the scale by looking at the person mowing the lawn on the right-hand side of the photo. The 144 blades were made of cedar wood and the large panel on the left was designed to place the rotor in a good position in relation to the wind. Brush also worked on batteries to store the generated electricity. A simplified version would become a familiar sight on American farms, where wind turbines were used to pump water for irrigation, either through a piston or an electric motor.

8. Dams for Power

The first dams date back to antiquity (Egypt, Mesopotamia). But it was not until the middle of the 19th century that architectural techniques emerged to guarantee their stability, and until the beginning of the 20th century that powerful turbines were introduced to convert the energy of the flowing water into electricity (known as “white coal”). Structures of this kind were first used in the Italian, French and Swiss Alps. The dam became a symbol of the power of nations, enabling them to increase their and stimulate their economy. In the early 1930s, the Tennessee Valley Authority dams, built as part of Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal, brought a poverty-stricken region back to life. In the early years of the Soviet Union, many monumental dams were built in Siberia and on the bloc’s great rivers (as shown here in Zaporizhia, on the Dnieper, in 1932). Construction was launched on the Aswan Dam on the Nile in 1960 by Colonel Nasser, in what was seen as an affirmation by young decolonized nations.

9. The Cost to the Environment and Heritage

Today, hydro is the most widely used renewable energy source, combining power and reliability, despite seasonal variations. The electricity generated is very flexible, meaning that it can respond to fluctuations in demand. However, constructing a dam is very disruptive to the environment and to the lives of the people living along the banks of the river. This was seen in China during the construction of the largest dam to date, the Three Gorges Dam on the Yangtze River. Building dams in the Amazon or in Southeast Asia brings economic progress but damages natural heritage sites at the same time. In France, in 1952, the construction of the Tignes Dam in the Alps was the subject of much public controversy. The old village had to be submerged under water. Many farms were also destroyed, and the cemetery had to be moved (in the photo, residents of Tignes remove coffins before the dam is flooded).

10. Semiconductors, Transistors and Photovoltaic Cells

In 1953, physicists and chemists Gerald Pearson, Calvin Fuller and Darryl Chapin developed the first -based solar cell, which converted the Sun’s rays into electricity. Their invention was a direct result of their research on semiconductors. Semiconductors also form the basis of the transistor, a small component that would revolutionize the world. Photovoltaic (PV) panels were first used in space exploration. On March 17, 1958, six months after the launch of the Soviet Sputnik, the U.S. Navy sent the Vanguard I satellite into space, fitted with both an electrochemical battery and small solar panels (this photo shows the assembly of the rocket). The battery depleted in a few days, while the solar cells lasted for weeks.

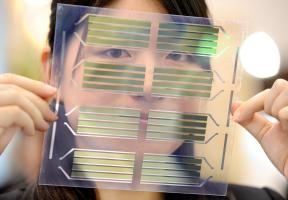

11. Photovoltaics Takes Off

It would take another 20 years or so for photovoltaic solar technology to reach an industrial level. In 1974, Japan launched the first photovoltaic power generation program, “Sunshine”. By the early 2000s, Germany was the hub of PV activity, until China, the United States and India entered the market, contributing to a spectacular drop in the cost of photovoltaic cells. The number of solar PV parks and installations on buildings soared. Solar panels lend themselves easily to distributed use, for example in Africa, in off-grid rural areas. As a result, photovoltaic technology has expanded access to electricity to nearly 90% of the world’s population. Research is constantly improving cell performance and configuration. In this photo, a flexible membrane, designed to fit the shape of rooftops, is presented at the InterSolar trade fair in Munich, Germany.

12. Concentrated Solar Power

Mouchot’s research in 1878 also lead to further studies in the field. In 1968, Félix Trombe developed a new model, the Odeillo solar furnace, which is still the largest in the world today. The parabolic mirror concentrates sunlight onto a focal point in the white tower, resulting in temperatures of over 3,500°C – hot enough to melt a diamond. However, heat from the sun can also be used to generate electricity indirectly in concentrated solar power plants. The principle is the same: thousands of small parabolic mirrors concentrate the Sun’s rays onto a central tower to heat a , which then drives a turbine. This type of power plant has been developed in Spain, the United States, South Africa and Morocco. Production remains low (50 times less than the world’s photovoltaic parks in 2019).

13. Wind Power, From Land to Sea

Windmills held their own against the steam engine until 1900. At that time, there were 30,000 in France and 18,000 in Germany. After the first oil crisis in 1973, there was an upsurge in the number of wind turbines, which were no longer isolated, but grouped together in increasingly large wind farms. Instead of being used locally, the electricity they generate is now fed into the major grids. Europe set the ball rolling, followed by countries with large areas of free land (United States, China, India), which gave the sector a considerable boost: by 2018, it accounted for more than 5% of the world’s electricity production (versus less than 2% for solar energy). wind power had been faltering for a long time due to its high costs and maintenance difficulties, but since 2010 it has experienced strong growth. Lagging behind Northern Europe, France now favors this type of wind turbine, which enjoys higher levels of public acceptance. This photo shows France’s first floating wind turbine off La Turballe, on the Atlantic coast, in September 2018.

14. Biofuels and Biogas

can be used to make biofuels and . The latter has been known about since the dawn of time. Bubbles of the substance, caused by the decomposition of plant and animal waste, naturally rise to the surface of marshes. As early as 1870, electric motors were powered by biogas in Europe. During the Second World War, the German army, which did not have easy access to oil, recovered it from farm manure to fuel its trucks. In India and China, millions of small “digesters” allow families to cook on camp stoves. In European countries, an as-yet small industrial sector has emerged to produce biogas, mainly methane, from organic waste or sewage sludge. This photo shows a biogas plant on the outskirts of Pretoria, South Africa, which uses cattle manure as a feedstock.

15. The Power Plants of the Future?

What will they burn instead of coal?’ ‘Water,’ replied Cyrus Harding. ‘Water decomposed into its primitive elements, by electricity, which will then have become a powerful and manageable force’. In the 1875 novel The Mysterious Island, Jules Verne, via his protagonist, envisions hydrogen becoming the fuel of the future. “Clean” hydrogen, which is produced by electrolysis of water, can be used in a to generate electricity or recombined to produce gas. It could therefore become a new fuel, produced, transported and traded around the world, as oil and natural gas are today. This image shows a model of an electrolysis-based hydrogen production unit on display at the Toshiba research center in Tokyo.

1. Wood, the First Energy Source

Humankind’s control of fire can be traced back by studying archaeological remains, including evidence of ancient hearths. It most likely dates back as far as 500,000 years in Europe, 800,000 years in the Middle East, and perhaps more than one million years in Africa. Prehistoric humans used the first form of , wood, which enabled them to warm themselves, create light, cook their food and keep wild animals away. In the Neolithic period (8500-3000 B.C.), our ancestors went beyond hunting and gathering and began to cultivate the land and domesticate animals, which provided a new source of energy for pulling plows and carrying loads. At the end of the Neolithic period, humans gradually learned to harness the of the wind and water and the of the Sun. With each new energy source mastered, humanity made rapid progress. Pictured here is a reconstruction of a prehistoric scene at the National Museum of Mongolian History in Ulaanbaatar.

2. Wind, the Source of Mobility

The construction of sailing boats, using the power of the wind, made it possible for people to expand their territories and discover the world. At its height, between 1500 and 1000 B.C., Egyptian civilization settled all along the Nile. In this photo, a mural discovered in the tomb of the royal scribe Menna shows a large funeral boat taking his body to Abydos, near Luxor, on the banks of the great river. During the same period, the Phoenicians sailed into the Mediterranean Sea from present-day Lebanon and gave rise to modern trade, exchanging goods with increasingly distant countries. Chinese civilization also began along the Yellow River, in 1600 B.C., before establishing the sea and land “Silk Roads”.

3. Water for Building Cities

The watermill is probably older than the windmill. It is mentioned by Vitruvius, a great Roman architect of the 1ST century B.C., in De Architectura. A 3rd century A.D. bas-relief in Hierapolis, Turkey, depicts an ancient water-powered machine using a system of connecting rods and cranks. According to a reconstruction of the design (see image), it operated a pair of saws intended to cut stone. In the following centuries, windmills and watermills would be developed to perform many functions, such as pumping water for cattle and land irrigation, sawing wood and making oils and flours. The windmill became a ubiquitous feature of the coasts of the Netherlands, Denmark, England and Germany, all of which have continued to develop wind technology.

4. Concentrated Energy from the Sun

The use of sunlight as an energy source came later than that of wood, wind and river currents. Legend has it that Archimedes was able to use parabolic mirrors to set fire to the Roman ships laying siege to Syracuse in 213 B.C., but the first real scientific experiments were not until the 18th century. In 1774, Horace-Benedict de Saussure from Geneva designed the “heliothermometer”, the predecessor of the solar collector, with a glass pane placed above an insulated box and a heat absorber. He even considered using double-glazing for better insulation. A little later, Antoine Lavoisier experimented with lenses that, by concentrating the Sun’s rays, could melt pieces of metal (as shown here).

5. The Two Forms of Solar Energy

In 1839, the 19-year-old (!) French physicist Edmond Becquerel discovered the , which allows to be produced from solar radiation. (His son, Antoine, would become a pioneer in .) However, it would take more than a century for this discovery to lead to real applications, after scientists had laid the foundations of nuclear physics and invented semiconductors. Others have attempted to use the heat of the Sun on an industrial scale. In 1878, Augustin Bernard Mouchot built an ingenious machine for the Universal Exhibition in Paris (shown here). It featured a 20-square-meter parabolic solar reflector with a steam engine at its center. Unfortunately, it did not generate a lot of power. Research into solar thermal energy was soon overshadowed by fossil fuels such as and later oil, which are much more efficient.

6. A Truly Brilliant Trailblazer

A Danish meteorologist, Poul La Cour (1846-1908), is considered the pioneer of . He was also one of the first to take an interest in the issue of electricity storage to overcome the problem of intermittency, and he had the idea of using as an intermediate . All of this makes him a true pioneer, especially since he also laid the foundations for telephony. With wind power, La Cour sought to bring electricity to the countryside to improve rural people’s working conditions and to prolong activity during the long winter nights, for example for education. In the beginning, he tried to generate electricity via the country’s many conventional windmills. Then he discovered that by using a blade shape for the sails and reducing their number, it was possible to improve their efficiency.

7. How the Wind Turbine Got Its Shape

Finding the right shape for a wind turbine was a long process. The Ohio-born American Charles F. Brush was instrumental in this process, building what is considered to be the first modern wind turbine in his home in Cleveland in 1888. However, it was not very efficient: the 36-ton machine had a capacity of just 12 kilowatts (the average wind turbine today has a capacity of 2,000 kilowatts). You can get an idea of the scale by looking at the person mowing the lawn on the right-hand side of the photo. The 144 blades were made of cedar wood and the large panel on the left was designed to place the rotor in a good position in relation to the wind. Brush also worked on batteries to store the generated electricity. A simplified version would become a familiar sight on American farms, where wind turbines were used to pump water for irrigation, either through a piston or an electric motor.

8. Dams for Power

The first dams date back to antiquity (Egypt, Mesopotamia). But it was not until the middle of the 19th century that architectural techniques emerged to guarantee their stability, and until the beginning of the 20th century that powerful turbines were introduced to convert the energy of the flowing water into electricity (known as “white coal”). Structures of this kind were first used in the Italian, French and Swiss Alps. The dam became a symbol of the power of nations, enabling them to increase their and stimulate their economy. In the early 1930s, the Tennessee Valley Authority dams, built as part of Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal, brought a poverty-stricken region back to life. In the early years of the Soviet Union, many monumental dams were built in Siberia and on the bloc’s great rivers (as shown here in Zaporizhia, on the Dnieper, in 1932). Construction was launched on the Aswan Dam on the Nile in 1960 by Colonel Nasser, in what was seen as an affirmation by young decolonized nations.

9. The Cost to the Environment and Heritage

Today, hydro is the most widely used renewable energy source, combining power and reliability, despite seasonal variations. The electricity generated is very flexible, meaning that it can respond to fluctuations in demand. However, constructing a dam is very disruptive to the environment and to the lives of the people living along the banks of the river. This was seen in China during the construction of the largest dam to date, the Three Gorges Dam on the Yangtze River. Building dams in the Amazon or in Southeast Asia brings economic progress but damages natural heritage sites at the same time. In France, in 1952, the construction of the Tignes Dam in the Alps was the subject of much public controversy. The old village had to be submerged under water. Many farms were also destroyed, and the cemetery had to be moved (in the photo, residents of Tignes remove coffins before the dam is flooded).

10. Semiconductors, Transistors and Photovoltaic Cells

In 1953, physicists and chemists Gerald Pearson, Calvin Fuller and Darryl Chapin developed the first -based solar cell, which converted the Sun’s rays into electricity. Their invention was a direct result of their research on semiconductors. Semiconductors also form the basis of the transistor, a small component that would revolutionize the world. Photovoltaic (PV) panels were first used in space exploration. On March 17, 1958, six months after the launch of the Soviet Sputnik, the U.S. Navy sent the Vanguard I satellite into space, fitted with both an electrochemical battery and small solar panels (this photo shows the assembly of the rocket). The battery depleted in a few days, while the solar cells lasted for weeks.

11. Photovoltaics Takes Off

It would take another 20 years or so for photovoltaic solar technology to reach an industrial level. In 1974, Japan launched the first photovoltaic power generation program, “Sunshine”. By the early 2000s, Germany was the hub of PV activity, until China, the United States and India entered the market, contributing to a spectacular drop in the cost of photovoltaic cells. The number of solar PV parks and installations on buildings soared. Solar panels lend themselves easily to distributed use, for example in Africa, in off-grid rural areas. As a result, photovoltaic technology has expanded access to electricity to nearly 90% of the world’s population. Research is constantly improving cell performance and configuration. In this photo, a flexible membrane, designed to fit the shape of rooftops, is presented at the InterSolar trade fair in Munich, Germany.

12. Concentrated Solar Power

Mouchot’s research in 1878 also lead to further studies in the field. In 1968, Félix Trombe developed a new model, the Odeillo solar furnace, which is still the largest in the world today. The parabolic mirror concentrates sunlight onto a focal point in the white tower, resulting in temperatures of over 3,500°C – hot enough to melt a diamond. However, heat from the sun can also be used to generate electricity indirectly in concentrated solar power plants. The principle is the same: thousands of small parabolic mirrors concentrate the Sun’s rays onto a central tower to heat a , which then drives a turbine. This type of power plant has been developed in Spain, the United States, South Africa and Morocco. Production remains low (50 times less than the world’s photovoltaic parks in 2019).

13. Wind Power, From Land to Sea

Windmills held their own against the steam engine until 1900. At that time, there were 30,000 in France and 18,000 in Germany. After the first oil crisis in 1973, there was an upsurge in the number of wind turbines, which were no longer isolated, but grouped together in increasingly large wind farms. Instead of being used locally, the electricity they generate is now fed into the major grids. Europe set the ball rolling, followed by countries with large areas of free land (United States, China, India), which gave the sector a considerable boost: by 2018, it accounted for more than 5% of the world’s electricity production (versus less than 2% for solar energy). wind power had been faltering for a long time due to its high costs and maintenance difficulties, but since 2010 it has experienced strong growth. Lagging behind Northern Europe, France now favors this type of wind turbine, which enjoys higher levels of public acceptance. This photo shows France’s first floating wind turbine off La Turballe, on the Atlantic coast, in September 2018.

14. Biofuels and Biogas

can be used to make biofuels and . The latter has been known about since the dawn of time. Bubbles of the substance, caused by the decomposition of plant and animal waste, naturally rise to the surface of marshes. As early as 1870, electric motors were powered by biogas in Europe. During the Second World War, the German army, which did not have easy access to oil, recovered it from farm manure to fuel its trucks. In India and China, millions of small “digesters” allow families to cook on camp stoves. In European countries, an as-yet small industrial sector has emerged to produce biogas, mainly methane, from organic waste or sewage sludge. This photo shows a biogas plant on the outskirts of Pretoria, South Africa, which uses cattle manure as a feedstock.

15. The Power Plants of the Future?

What will they burn instead of coal?’ ‘Water,’ replied Cyrus Harding. ‘Water decomposed into its primitive elements, by electricity, which will then have become a powerful and manageable force’. In the 1875 novel The Mysterious Island, Jules Verne, via his protagonist, envisions hydrogen becoming the fuel of the future. “Clean” hydrogen, which is produced by electrolysis of water, can be used in a to generate electricity or recombined to produce gas. It could therefore become a new fuel, produced, transported and traded around the world, as oil and natural gas are today. This image shows a model of an electrolysis-based hydrogen production unit on display at the Toshiba research center in Tokyo.

Our most popular content

Our most popular content

See all